Thoughts on copyright questions as 3D printing comes of age

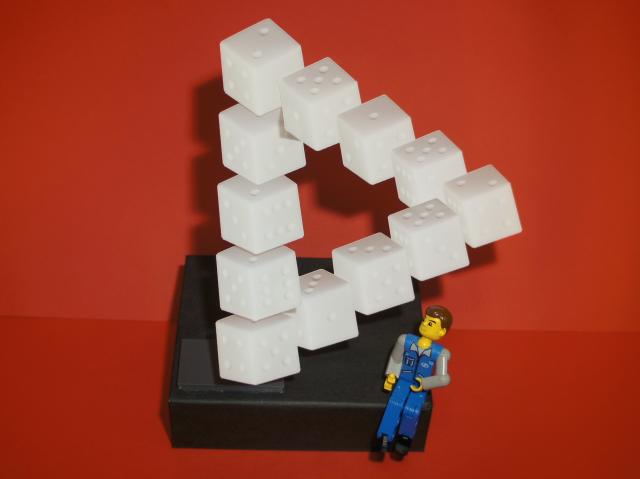

Peter Hanna of Ars Technica wrote an article on copyright implications once 3D printing becomes more common. Surprisingly, when opening the article I saw a picture of myself (I had nothing to do with that, but I don’t object, either :))

The article is an interesting read, with some good observations concerning a pending conflict about IP in 3D content. Also, the discussion that followed is very interesting to read. My favorite response is this one by Conner_36: “This damn internet thing… it causes so many problems.”. Another, more elaborate response about stifling innovation by RikuoAmero really sums up much of why I think strong IP is bad. Also, I liked this response by hpsgrad:

“Equally to the point, 3D printing has the potential to create a totally different, post-modern mode of production. Why should we cripple this new new mode of production in an attempt to protect the current one?”

“Alternatively, you might be afraid that 3D-printing has the potential to make it too easy to make stuff, and that as a result, nobody would bother to create new, better, and genuinely creative things. Again, I think that this is absolutely insane. The thought that people would stop making stuff because it’s too easy to make stuff is simply bizarre.”

Through this blog I’d like to add some perspective the discussion. Copyright and patents are ONE answer to a bigger question: How do we structure the provisioning of goods in society? Obviously, there are other answers possible, but the law is very slow to change and historically, for intellectual property (IP), has only gone in the direction of being MORE restrictive.

It is important not to forget why society grants intellectual monopolies (a monopoly better covers what IP really is). While policymakers are influenced strongly by those who profit from intellectual monopolies, there used to be a valid reason for society to accept these artificial monopolies on replicating ideas and designs. The rationale used to be: if inventors would not have the profit driven incentive, these inventions would not be created. This dilemma is more and more becoming a false dilemma. I recommend watching Glyn Moody’s talk on this subject [1] and, also, Benkler’s “Wealth of Networks” [2] for a scientific treatment of this false dilemma. Today, innovation is becoming democratized, even more so by 3D printers and other digital fabrication technologies. Anyone with internet access and an idea can design an innovation and print it in 3D on an affordable machine such as an Ultimaker or have Shapeways or Ponoko make it for them. Because the design is digital, groups can collaboratively create better designs. Moreover, it scales better than an R&D department: in the RepRap community about 200 full time equivalents are spent, voluntarily, to make a better 3D printer that can print itself. These are already more man-hours worked than the biggest player in the 3D printer industry could afford. But the big difference is: the 200 FTE’s in the RepRap community are contributed by thousands of different individuals instead of a small team that works full-time [3]. Creativity, and the innovation that flows from it, works best when a heterogenous population of passionate individuals interact. Moreover, a big group that can openly discuss problems has access to a much broader set of knowledge. This is the reason why communities such as Thingiverse works so well and why licenses that embrace the freedom to copy and derive are important for innovation to flourish. This is what is called social production, an alternative to firm and market based production. In social production public good aspect is preserved.

We’ve been led to believe we’re dependent on those who invent and produce on our behalf, while at the same time the tools to invent and produce are increasingly within our reach. In many cases, the user has the potential to create a better product [4], because it can be tailored to his/her needs instead that of the average wishes of a market segment that has a profit expectation. In markets with varied needs, there is under-provisioning because the tools or rights to derive were not available (one example of “market failure”). Nowadays, preserving these freedoms becomes more important to stimulate innovation than to restrict the flow of knowledge in favor of exclusive right holders. Those who sit on their knowledge in order to exploit it, will never improve it as fast as those who share, interact and mingle their knowledge with others. The same goes for design knowledge and we’re missing out on a lot of design improvements.

Most objects made by manufacturers were originally developed by users, but it is not apparent where manufacturers get their inspiration from. In many industries, there is a systemic bias to think manufacturers are in most cases the source of innovation [5]. In many cases the most appropriate role of manufacturers is that of actual manufacturing, not invention.

We need to reconsider the role of intellectual property and to identify and counter policy bias that is suboptimal in terms of provisioning of goods in society (see also [6]). The role of governments should always be to preserve the flow of knowledge, not to promote ownership and the right to exclude for the sake private profit. If ideas are abundant when protection is not offered, why do we want to create all this friction? The fashion industry is an example where virtually no protection is available [7]. Any disruptive technology has led to a battle between old industries that want to maintain their outdated business models. The problem is that they are organized in influencing policy and even public opinion (to copy is to steal!). We should not expect policymakers to fully understand the non-rival nature of digital goods until we use it to create increasingly valuable alternatives. The emerging field of collaborative free and open design is a great example to enlighten them (details are in [3]).

[1] Glyn Moody on Intellectual Monopolies at FSCONS 2011.

[2] Benkler, Y. The Wealth of Networks, Yale University Press, 2006: “By lowering the capital costs required for effective individual action, these technologies have allowed various provisioning problems to be structured in forms amenable to decentralized production based on social relations, rather than through markets or hierarchies.”

[3] E. de Bruijn, On the viability of the Open Source Development model for the design of physical objects. 2010

[4] Chapter 5: “Users low cost innovation niches” PDF

[5] E. von Hippel, Sources of Innovation by Eric von Hippel – Oxford University Press, 1988

Download courtesy of Oxford University Press at http://web.mit.edu/evhippel/www

[6] von Hippel, E. and Jong, J. P. J. D. (2010). Open, distributed and user-centered: Towards a paradigm shift in innovation policy

[7] http://www.ted.com/talks/johanna_blakley_lessons_from_fashion_s_free_culture.html

[Erik] The rationale used to be: if inventors would not have the profit driven incentive, these inventions would not be created

[Anónima] That’s only part of it. The other main reason is that some people tend to keep their knowledge secret so patents are about giving an incentive to make knowledge publicly avalaible.

Thanks to the patent system, the inventor has a strong incentive to give a complete description of the invention so every body can learn and experiment (non commercial use) and make improuvments.

It’s important to remember that patent documents are avalaible for free unlike some scientific papers 😉

[Erik] Nowadays, preserving these freedoms becomes more important to stimulate innovation than to restrict the flow of knowledge in favor of exclusive right holders.

[Anónima] Patents don’t restrict the flow of knowledge: there are free easy to consult documents.

http://www.epo.org/searching/free/espacenet.html

Espacenet offers free access to more than 70 million patent documents worldwide, containing information about inventions and technical developments from 1836 to today.

[Erik] Those who sit on their knowledge in order to exploit it, will never improve it as fast as those who share, interact and mingle their knowledge with others.

[Anónima] That could very well be true. But if the improuvment implies an inventive step, then there is not a problem of patent infringment unless you still need to use the original invention.

In that case you can get a fair deal of cross patents.

Patents protect against copying not against worthwile improuvments.

[Anónima] Patents don’t restrict the flow of knowledge: there are free easy to consult documents.

I know more than a few companies that have a policy not to read others’ patents, because being in the knowing make the infringement worse. There’s a reason for this: many ideas are invented several times, independently. While the first person can claim the rights to the invention that the others have likewise created independently, the others are infringing when they utilize their own invention. Of course it makes sense that their sanctions are reduced when they didn’t know about it. It’s awkward enough that they can get punished for being inventive. But it’s hard to prove that they didn’t just copy the invention because of the patent. This is another dilemma that patents create.

Also, I consider reading patents that are still valid as similar as learning to use a very expensive software tool, that you could never afford. This means that you’ll force yourself to relearn another package or be infringing when the trial period expires.

I don’t think that the average garage based inventor reads patents in order to be able to invent.

[Anónima] Espacenet offers free access to more than 70 million patent documents worldwide, containing information about inventions and technical developments from 1836 to today.

I think that it’s great that there are so many old patents available, but the extreme amounts of patenting nowadays can hardly be justified, even if they are published, this knowledge contains serious risks when you adopt it.

[Anónima] That could very well be true [That those who interact, develop their knowledge faster]. But if the improuvment implies an inventive step, then there is not a problem of patent infringment unless you still need to use the original invention.

We’ll you can still infringe claims that are upheld in court. And you don’t know this in advance, so the risk keeps people and businesses out of competing in a certain innovative market because of bigger players that can afford to file, or worse, acquire patents. This especially keeps out smaller new entrants in a market. We all know that this is a bad thing for the evolution of an industry and eventually for the consumer.

[Anónima] … Patents protect against copying not against worthwile improuvments.

For one I think that the word ‘protect’ is very inaccurate. Restrict is more appropriate.

Gerry Barnett recently also wrote an interesting blog post on this subject:

http://rtei.org/blog/2011/04/26/ip-in-3d-printing-2/